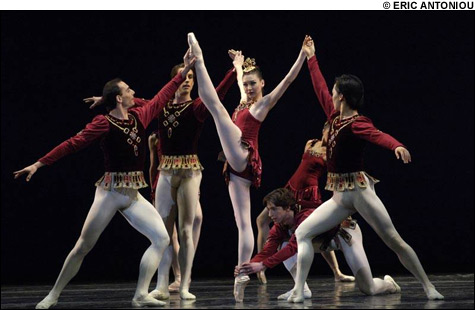

RUBIES: Kathleen Breen Combes was too much for her hunters in the Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors section; she also impressed Alastair Macaulay of the New York Times.

|

In 1967, George Balanchine created Jewels for New York City Ballet, and in short order this evening-length triptych — Emeralds, Rubies, and Diamonds — became the crown jewel of 20th-century dance, three ballets that add up to one, glitter that’s also gold, a “plotless” work that’s really a bottomless well of stories. Boston Ballet has staged Rubies on four previous occasions, but never Emeralds or Diamonds. Now it’s finally offering a complete Jewels (at the Wang Theatre through March 8), and if Emeralds is so far a little pale, Rubies and Diamonds confirm the company’s international stature, the latter crowned by three laceratingly intimate performances from Kathleen Breen Combes and Yury Yanowsky. Here’s how the first weekend shook out.

In 1967, there were just six sections to Emeralds; in 1976, after Suzanne Farrell had left NYCB and then returned, Balanchine added the “Epithalamion” from Shylock and, as the final section, Fauré’s music for the death of Mélisande. The 10-woman corps disperses; the two lead couples and the pas de trois man and two women process in funereal majesty. The lead men exchange partners; then the pas de trois ladies run out at the back, and the lead women follow them. The three men go to one knee and extend their right hands — only they’re facing opposite to the direction the ladies exited. Women (Farrell) one way, the Eternal Feminine the other.

The first woman has to be liquid (Balanchine set this part on Violette Verdy), and Larissa Ponomarenko, with an attentive Nelson Madrigal as her partner, was. Opening night, Yury Yanowsky and Lorna Feijóo looked ill-matched and ill at ease; partnered with Madrigal on Sunday, Feijóo caught the flow of the music better. Dancing with Carlos Molina Thursday and Lorin Mathis Sunday, Erica Cornejo was rapturous in the Mimi Paul second-lady role. The Boston Ballet Orchestra under Jonathan McPhee made palpable the contrast between oboes and horns, hunted and hunter, women and men.

RUBIES | This one is New York City and America; its backdrop is midnight blue, and its element is fire, with Igor Stravinsky’s jazzy, circusy Capriccio for Piano and Orchestra changing its time signature (2/4, 4/4, 3/4, 3/8, 5/16 — you get dizzy) almost as fast as women are alleged to change their minds. Available and not, the Lipizzaner ladies prance and preen and flaunt their Rockette legs; the Tall Girl displaces her pelvis as if she were a Picasso while showing off every facet of her anatomy; the Adam and Eve couple skip rope, ride broncos, tango, and run in place. (In the last movement, the guy runs with the four hunters, but it’s not clear whether he’s the leader of the pack or its quarry.)

All the pony stepping underlines the idea that the object of the Emeralds hunt is the unicorn. (We know from her autobiography, Holding On to the Air, that Balanchine had taken Farrell to see the Lady and the Unicorn tapestries at the Cluny Museum in Paris, and that she also visited the Hunt of the Unicorn tapestries at the Cloisters in New York.) As Stravinsky’s first movement reprises its apocalyptic opening moment, the Tall Girl is surrounded and poked at by four men, just as the unicorn is at the Cloisters, but she breaks free as they kneel. (Balanchine might also have had in mind Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors.) It’s not till the Diamonds pas de deux that the lady tames, and is tamed by, Love. The last of the six Cluny tapestries is titled “À mon seul désir”; for Balanchine in 1967, that was Farrell.