.jpg)

FAMILY TREE: This Zhang Huan self-portrait belongs to a series of several photos in which the artist’s face is slowly and completely covered. |

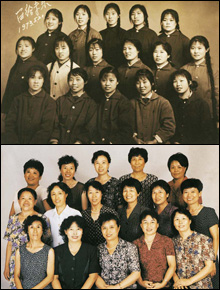

"Mahjong: Contemporary Chinese Art from the Sigg Collection" at Salem's Peabody Essex Museum opens with a pair of interesting choices. Liu Xiaodong's Eating (2000), an oil painting of shirtless surfside Chinese men standing behind a pile of crabs on a boulder, will appeal to New England cultural affectations. But it's Hai Bo's They Recorded for the Future (1999) that sums up the show's intentions. It's a diptych of posed photographs, one a black-and-white portrait of 16 women donning dark-colored Communist-era garb, the other — hung directly beneath it — showing the same women in colorful day dresses and blouses 25 years later. Executed here with surprising wit, the concept of re-examining the past by way of the present is at the very heart of "Mahjong."Uli Sigg was the Swiss ambassador to China and Korea for much of the 1980s and '90s. He and his wife became patrons of Chinese art and artists, and as such they were able to buy large amounts of cutting-edge work. Their collection is a vast and brilliant assembly of Chinese works created in the last 40 years, and by juxtaposing it with its own outstanding permanent collection of Oriental and Asian work, the Peabody Essex has provided an exciting and edifying context. These contemporary pieces teem with perspectives bred from Chinese streets and rural villages, reflecting immediate reactions to a speedy Westernization, thousand-year-old artistic traditions entrenched in Chinese culture, and political and social change on a massive scale.

"Mahjong" marks the debut of PEM's first contemporary curator, Canadian-born Trevor Smith. Formerly the curator in residence at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard, Smith was also curator at the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York from 2003 to 2006. "In the game mahjong, tiles are shuffled and combinations are made anew," he tells me over a cup of coffee in the museum's café. "As a curator, I'm really fascinated by the potential that one has to make new connections for people, or, in a museum like this, to have the opportunity to lay out these incredible contemporary pieces next to historical work."

Installed in a small side gallery, Wang Jinsong's Standard Family (1996) is a grid of dozens of framed photos, each featuring an image of a standard three-person Chinese family — father, mother, and child — posing in front of a red background. The color of luck and good fortune in Chinese culture, red now represents not only the country's Communist inheritance but the blood spilt enforcing the socialist republic's one-child policy. Effortless and subtle in its presentation, Wang's work also raises the question of what the future holds for Chinese youth. In Weng Fen's photo On the Wall — Guangzhou (II), a young schoolgirl sits on a ledge gazing up at a seemingly monstrous skyscraper — an allusion to the country's mad dash to modernity and Westernization. Xu Bing's Himalaya Drawing (2000), in which Mandarin symbols for "mountain" and "water" are drawn together in ink on Nepal paper to form rolling hills and lakes, subverts (and also revisits) shan shui, a traditional form of Chinese landscape painting practiced since the 10th century.

THEY RECORDED FOR THE FUTURE: Nothing so dramatically captures the spirit of the Peabody Essex show as Hai Bo’s diptych. |

The decision to relegate all works with images of Chairman Mao into a single dead-end gallery with one entrance reinforces the show's themes. As important as Mao is to the discussion of China's cultural change, his face conjures endless associations, and this image, after being repeated for years in Communist propaganda and Chinese Pop Art, has become almost trite — like a Che Guevara T-shirt at Urban Outfitters. The "Mao and Beyond" gallery does convey the country's political turmoil, however. Large-scaled photo-realist paintings from the early 1970s feature images of "the happy peasant" constructing bridges and other projects, building something greater than himself. The workers' bodies appear to lurch ahead, as if they were propelling themselves into the future; sporting rosy cheeks and smiling faces, they might have been painted by Norman Rockwell during the Cultural Revolution. Chain (1979), a wooden wall sculpture by Wang Keping in which a hand covers the mouth of a bust with a chain around its neck, reflects a different and grimmer reality.Then there's the conversation "Mahjong" carries on with the permanent galleries. Liu Jianhua's Obsessive Memories (2003), an installation of several porcelain figures of women sans heads and arms, finds a home among the porcelain objects. Wang Jin's The Dream of China (1997), a transparent polyvinyl and monofilament version of a traditional Chinese robe, is suspended near textiles within the Chinese-art collection. But it is the PEM's Yin Yu Tang, a 200-year-old Qing Dynasty house plucked from Southeastern China and rebuilt for the museum, that really puts the contemporary show into focus.