Gina Gionfriddo’s After Ashley; A.R. Gurney’s Screen Play

The American media have long pigged out on titillation and tragedy. And in After Ashley (presented by Company One at the BCA through November 18), Gina Gionfriddo has written a frighteningly funny work about that particular eating disorder. The play, which debuted in 2004 at the Humana Festival of New American Plays and went on to an Off Broadway run starring Kieran Culkin and Anna Paquin, mercilessly satirizes the way in which both media and victims exploit catastrophe — in this case turning one wounded teen into a coruscating vigilante for frank remembrance, however lacking it might be in hearts, flowers, or political correctness. And if Company One hasn’t decorated the Boston premiere with movie stars, it fields a mostly excellent non-union cast that makes credible even Gionfriddo’s most outrageous leaps — and she moves from Dr. Phil’s territory to Jerry Springer’s to Paris Hilton’s before she’s done.

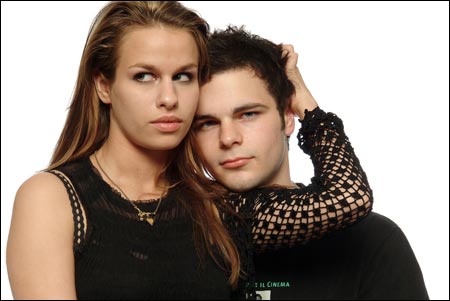

AFTER ASHLEY: Pigging out on titillation and tragedy. |

We meet the title character in the first scene, which is set in 1999 and finds this unhappy 35-year-old mother of a 14-year-old boy who’s home sick with mono making him even sicker with her inappropriate talk of drugs and sex and her own romantic restlessness. Poor son Justin does his best to hide under a blanket as, in Shawn LaCount’s sharp production, Ashley prods his personal space on a too-small couch. When education-reporter dad Alden, a font of liberal unctuousness, arrives, you can see why Ashley’s unfulfilled. For one thing, she’s as blunt as he is fuzzy. When Alden announces he’s met a homeless schizophrenic and hired him to do yard work, she opines that sometimes people are homeless because they’re lazy, adding for good measure that she’s met battered women who would provoke her to violence.

By the play’s second scene, Ashley has been raped and murdered by the handyman, who was off his meds. It’s three years later, and Alden has written a bestselling memoir titled After Ashley. The whole world has listened to Justin’s 911 call, in which he refused to leave his dead mother even though the killer might still be lurking. And father and resentful son (who has been through drink, drugs, and therapy) are appearing on a TV talk show to discuss their healing. As it happens, host David Gavin got his gig by milking his own tragedy: he is the deadbeat dad of a murdered child whose death he parlayed into a career and a message: “Don’t postpone love.” Alden’s message, sneers Justin, might as well be “Bring the homeless home.” Certainly Alden isn’t bitter about his wife’s murder: he dedicated his book to the killer’s mother. And glib, booming David pronounces the sentimental, highly sanitized After Ashley an “American epic tragedy” reflective of the 9/11 zeitgeist, in which our collective sense of safety has gone up in the smoke of the Twin Towers.

Before you know it, Alden has his own talk show, in which video of a sparkling ocean leads into interviews with victims of sex crimes followed by “tasteful” re-enactments and the dispensing of safety tips. Father and son have relocated to Florida, because it’s cheaper to shoot the show there. Justin is holed up in a sparsely furnished apartment financed by an allowance from painstakingly understanding dad. And the teen has taken up with a goth college girl named Julie, who came on to him because of his ghoulish celebrity as “The 911 Kid.” But when Alden and David come up with a plan to plaster Ashley’s name on a home for battered women staffed by volunteers called Ashley’s Angels and wearing little purple lapel wings, Justin pulls out his secret weapon and all hell breaks shockingly and hilariously loose.

ADVERTISEMENT

|

What’s most ingenious about After Ashley, which makes use of live as well as recorded video, is the way in which it draws the audience into its scathing send-up of voyeurism. (Sure, we want to watch; roll the tape!) Company One handles this aspect adeptly enough. But what’s most impressive about the production is the terrific performance of two young actors, students at Suffolk University and Boston Conservatory respectively, as Justin and Julie. Ed Hoopman nails Alden, whose fervent goals are political correctness, do-gooder liberalism, and psychological understanding, so long as they don’t get in the way of his opportunism. Kelly Lawman makes the most of Ashley’s loving, ditzy fragmentation. And Naheem Garcia combines sonorous polish with street toughness as broad-gesturing David. But Ana Nogueira, as 20-year-old older woman Julie, shy and precocious at once, and Jonathan Orsini, as the hilariously scathing if hurting Justin, are as brazenly real as Alden’s carefully deployed grief is phony.