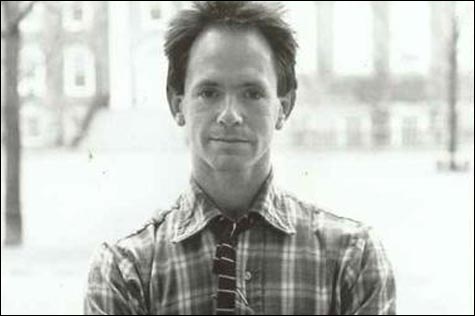

SUBTLE PERFECTION: Peter Ivers was endlessly accomplished, with legions of devoted friends. Now, 25 years after his mysterious murder, the lost legacy of his life is being reclaimed. |

Peter Ivers was freakishly gifted on the harmonica. None other than Muddy Waters, in the midst of a 1968 jam at Cambridge Blues Club, proclaimed him to be “the greatest harp player alive.” His debut album, Knight of the Blue Communion (Epic, 1969), is considered a forgotten masterpiece of outré psychedelia. As a student technical director and score writer at Harvard’s Loeb Theatre, he was close with such actors as John Lithgow, Tommy Lee Jones, and Stockard Channing. His best friend was Harvard Lampoon editor and (National Lampoon founder) Doug Kenney, who’d go on to co-write Animal House and Caddyshack. His band opened for Fleetwood Mac. He was asked by David Lynch to co-write “In Heaven (The Lady in the Radiator Song)” for Eraserhead. He was good pals with John Belushi and Harold Ramis. As co-creator of the LA-based UHF-format TV show New Wave Theatre, he brought punk bands, including Dead Kennedys and the Circle Jerks, into the living rooms of America.

You’ve probably never heard of Peter Ivers. But the Brookline-born, Roxbury Latin- and Harvard-educated free spirit — a sort of Zelig of the late-’60s-to-early-’80s pop-cultural scene, who was murdered in 1983 — was a one-of-a-kind talent, says Josh Frank, co-author, with Charlie Buckholtz, of In Heaven Everything Is Fine: The Unsolved Life of Peter Ivers and the Lost History of New Wave Theatre (Free Press). “If anyone’s story deserves to be told, it’s Peter’s.”

Ivers was endlessly accomplished. He was well-loved by all who knew him, be they Hollywood high-rollers or bile-spitting punks. And his promise was snuffed out far too soon. “He did more in his 36 years than any pop star that gets press daily for brushing their teeth,” says Frank. “He inspired all of the top people from the world of film and TV and music. You name anybody, and they either knew Peter or their best friend knew Peter. And the reason he didn’t get a chance to shine was not because he was less talented than the others; in fact most of them would say, ‘Compared to Peter, I’d done nothing back then.’ But then he was murdered.”

‘What do we do, Starsky?’

On March 3, 1983, in an artist’s loft in a seedy section of Los Angeles, Peter Ivers was bludgeoned to death in his bed. Just hours later, not long after the LAPD had first arrived at the murder scene, the loft was descended upon by dozens of Ivers’s Hollywood friends.

Harold Ramis was there. So was New Wave Theatre’s co-creator, David Jove. Frank writes of actor Paul Michael Glaser arriving at the scene, where baffled police stood by, near-panicked by the weeping, fainting crowds. “Overwhelmed by the throng, losing once and for all whatever grasp of the situation they may have had . . . the two officers are hit with the full weight of the knowledge that they have no idea what this place is, who this person was, what it all means, or how to proceed. Glaser opens his mouth, but before he can get a question out, or even a word, one of the officers shouts his own question over the mob’s raucous din: ‘What do we do, Starsky?’ ”