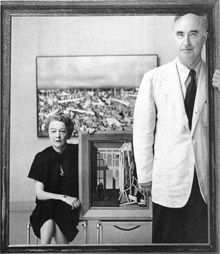

TWO OF A KIND Kay Sage and Yves Tanguy, here shot for Time magazine on the occasion of their joint exhibition at the Wadsworth Atheneum in 1954. |

Kay Sage and Yves Tanguy liked each other's paintings of surreal rocky blobs rising on vast, empty landscapes before they met in Paris in 1938, and they liked each other when they were introduced. By the following spring they were a couple, but they pursued independent careers, only showing together once during their lives. "Double Solitaire" at Wellesley College's Davis Museum (106 Central Street, Wellesley, through January 15) reunites them.

SLIDESHOW: "Double Solitaire" at Davis Museum + "Kindred Spirits" at Yezerski

Organized by the Katonah Museum of Art in New York and the Mint Museum in North Carolina, the intriguing show features some 44 paintings. The resemblance between the couple's art is obvious. Inspired by the Italian painter de Chirico, they both painted wastelands suffused with feelings of loneliness and abandonment.

Paris was on the edge of war in '38. "Even as early as 1934, I had begun to recognize certain fascist symptoms in France," Tanguy recalled in 1945. "When I began to see hints of impending trouble in Europe, I made up my mind to leave the old world as early as possible." Sage (1898-1963) left for New York in October 1939, and arranged for Tanguy (1900-1955) to follow the next month, shortly after Germany invaded Poland.

They settled in Connecticut after they married in 1940 — and a gloom came into Sage's paintings. The foreground of White Silence (1941) features a jagged bone or a shattered airplane wing, with veins and red fringe resembling shredded flesh. Vacant buildings, shrouded forms, and collapsed architectural framing appear again and again in her paintings of the '40s and '50s, like recurring nightmares of war.

Tanguy's 1943 painting Through Birds, Through Fire, But Not Through Glass is a curious tower of blobs and spokes and stones, some of which seem cling-wrapped. His late masterpiece, 1954's Multiplication of the Arcs, depicts a dazzling accumulation of piled, smooth stones and fallen, broken columns. It's teeming but barren under his usual stark light, like sun breaking through storm clouds.

The exhibit aims to show how the couple influenced each other. She may have painted wastelands because of him. He may have moved his forms into the foreground and turned them into enigmatic architecture because of her. Or not. It's unclear. But Sage clearly was devastated when a cerebral hemorrhage felled Tanguy in 1955. Then her eyesight began to fail, and she gave up painting. In 1963, she shot herself in the heart. "The first painting by Yves that I saw, before I knew him, was called I'm Waiting for You," the suicide note read. "Now he's waiting for me again — I'm on my way."

In "Two Kindred Spirits" at Howard Yezerski Gallery (460 Harrison Avenue, Boston, through November 15), curator Trevor Fairbrother pairs drawings by Marsden Hartley (1877-1943) with John O'Reilly's recent Hartley-inspired collages. O'Reilly is attracted to Hartley's masterly, roughhewn late style, begun in his summers painting the boulder strewn fields of Dogtown in Gloucester in the '30s, as well as his sad end as a lonely, broke, closeted gay man seeking a place for himself in his native Maine. The Hartley drawings, on loan from Bates College, aren't his best, but awkward sketches of fey bare-chested fishermen or a scantily-clad wrestler reveal a heartbreaking longing.