This, according to Romero, demonstrates a lack of perspective on the part of those who seek identity and importance by immersing themselves in the virtual world. “I was concerned about this media explosion, alternate media, the blogosphere,” he explains. “It struck me that, in the world now, everyone’s a camera, everyone’s a reporter. It all has a sort of power, and people believe and buy into it. It seems to me any lunatic could get on there and suddenly have a following. I’ve joked about how if Jim Jones had a blog, we’d have millions of people drinking Kool-Aid.”

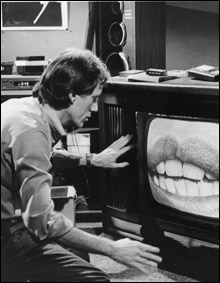

SIZE MATTERS: Mysterious media includes a pirate broadcast in Videodrome (above) and a corpse in Blowup.

|

Screen germs

Actually, they’ve been drinking the media Kool-Aid for some time. As with carbon monoxide and global warming, perhaps we’re just starting to figure out how bad the consequences might be. For decades, filmmakers have been pondering the effect of media — the rival forms of TV and video especially — on people. Is it a harmless, even beneficial diversion? Or a toxic plague?

In Being There (1979), Hal Ashby and writer Jerzy Kosinski’s classic parable of the television generation, a lifetime of drinking the Kool-Aid of the cathode ray doesn’t seem such a big handicap for the content-free protagonist Chance when he’s suddenly tossed on the street. True, he gets off to a rough start when he tries to change the station with his remote as he’s menaced by a gangbanger with a switchblade. But soon enough he’s embraced by the powers that be, who read Delphic wisdom into his blank slate, and eventually he becomes a prototype of Ronald Reagan. Creepy, perhaps, but still a happy ending.

But what if Kool-Aid’s effect is not so neutral, benign, or (as suggested by Being There’s messianic last scene) transcendent? What if, as suggested by cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard in his 1981 book Simulacra and Simulation (a copy of which can be seen on screen in The Matrix, which is probably just as good as reading it), they are instead directly “destructive of meaning and signification . . . ?” What if, by their very nature, the media undermine all those qualities traditionally associated with what it means to be a human being?

Or, to push the paranoia even further, what if the novelist William S. Burroughs was right when he said “The Word” — including the media and all language — “is literally a virus . . . an organism with no internal function other than to replicate itself.”

Sounds like a horror movie. In fact, several. A recent example that fits Burroughs’s formula with eerie exactness is The Ring (2002), in which a supernaturally conceived videotape not only kills people, but, like a virus, passes from one victim to the next by the replication process of a VCR.

From where did this pathogen emerge? In Tobe Hooper’s Poltergeist (1982, written by Steven Spielberg), an innocent child sitting rapt before a TV screen transforms it into a portal through which pass demented spirits of the dead, who terrorize the little girl’s contented suburban family. Was the demonic possession of Poltergeist a metaphor for the media explosion of cable and satellite TV that would ultimately give birth to Fox News and the Home Shopping Network?

Speaking of metaphors, leave it to David Cronenberg to crank up the malevolence an extra notch in Videodrome (1983). In that film, the unscrupulous operator of a seedy Toronto cable station wants to build up his ratings by programming edgy porn. He comes across a pirate broadcast of a show called Videodrome, which has no characters or plot but is simply 24 hours of apparently real torture and death. (Cronenberg’s version looks quaint compared with recent torture-porn cinema, or even Survivor: Micronesia.) Unfortunately, the program’s “content” (the “meat” McLuhan was talking about) masks a signal that mutates the cable operator into the “New Flesh,” a human/machine hybrid sporting a vaginal-like slot in his abdomen for receiving video cassettes that program him into an assassin.

Just in case the McLuhan references go unnoticed, Videodrome puts the man himself in the cast thinly disguised as the character Brian O’Blivion, who “never appears on TV except on TV” and is prone to such pronouncements as, “The television screen is the retina of the mind’s eye. . . . Therefore, whatever appears on the television screen emerges as raw experience for those who watch it. Therefore, television is reality, and reality is less than television.”

Remote possibilities

Add the Internet to O’Blivion’s equation and the world of today looks something like the one in Gregory Hoblit’s Untraceable (2008). A mad hacker has set up a Web site called “KillWithMe?” in which a hapless victim is set up in a Saw-like environment that grows more lethal as each visitor logs on. With each click, another searing heat light turns on, or more sulfuric acid drips into a vat. The FBI can’t trace the site’s location, nor can they haul in the culprit’s accomplices — the thousands of thrill-seeking voyeurs who somehow feel that the detachment and anonymity of the computer screen absolves them of culpability.