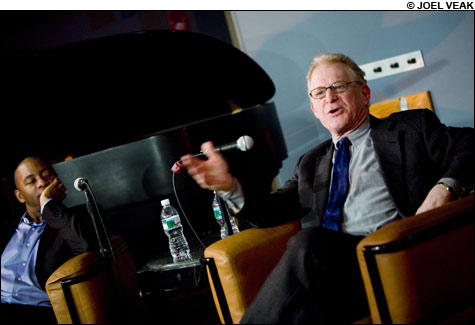

B&B: Marsalis and Blumenthal sparred over Mugsy Spanier.

|

Bob Blumenthal’s first book is out, and the wonder is that we didn’t get it sooner. Blumenthal, who’s written about jazz for almost 40 years, has long been one of the music’s authorities. He began writing for Boston After Dark in 1969 and stayed with its successor — the Phoenix — till 1989, when he became a correspondent for the Globe. In 2002, he went with Branford Marsalis’s Cambridge-based label, Marsalis Music, as creative consultant — a job that includes a bit of everything: A&R; writing and editing the company’s newsletter and, when called for, liner notes; and administering the “Marsalis Jams” education program in high schools and colleges. He’s written anthologized essays and more than a thousand newspaper articles and reviews; he’s also won two Grammy Awards for his liner notes.

Blumenthal’s book is deceptively modest in size and format. Jazz histories tend to be epic tomes. The generously illustrated Jazz: An Introduction to the History and Legends Behind America’s Music is a mere 192 pages. Published by HarperCollins as part of a Smithsonian paperback series of introductions to different disciplines, it’s meant as an overview. But it’s worth more than several of its heftier cousins. Blumenthal makes the usual trip: from ring shouts and blues and New Orleans up through “free” jazz and till almost yesterday (Maria Schneider and Norah Jones are in the last chapter). But his use of compression is a tonic. His five chapters leapfrog in two-decade increments — a way of keeping jazz’s ongoing story before us. As a critic, he’s always been able to see the specific detail and the grand arch of jazz history in simultaneous focus. Whatever the individual achievement — the evolutionary step — we never lose sight of its place in a multifarious social and musical history.

Blumenthal is as discerning as he is broadminded, and he takes a common-sense approach to the perennial jazz arguments about art versus entertainment, innovation versus tradition, and what is or isn’t jazz — the real thing as opposed to instrumental pop, the “hybrids that replace challenge with a bland background impersonality.” In a post-Wynton world, where the official definition of jazz seems to be more and more narrowly defined, Blumenthal sees its diversity as essential. His book is accessible enough for neophytes, but it will also pleasurably remind old fans of things they thought they knew.

“I wanted to avoid the relay-race view of jazz,” he tells me over a late lunch at Audubon Circle. “You know: Louis Armstrong hands the baton to Dizzy Gillespie who hands the baton to Miles Davis. One thing I liked about the Ken Burns documentary was that it showed that these guys never stopped running!” Jazz history is itself compressed, “front-loaded” in its years of invention and initial development. Blumenthal highlights a great moment: the June 1978 jazz party hosted by Jimmy Carter on the South Lawn of the White House, where the guest list represented not only the music’s complete stylistic scope (Benny Carter to Ornette Coleman) but also a moment of intense generational unity — from Eubie Blake (born 1883) to Herbie Hancock (born 1940). But the history of jazz stretches on, its origins receding farther into the past, and it’s no longer possible to represent all its generations at a single gathering.

“Jazz means different things at different times,” Blumenthal continues, “and as time passes, it means more.” Every generation — or at least, portions of every generation — trashes the previous one. The swingers hated bebop, the “moldy figs” of New Orleans and Chicago-style jazz thought big bands (even Duke Ellington!) were anti-jazz. “There were even people who thought King Oliver was ‘inauthentic’ because that’s not how jazz was played in New Orleans in 1916!”

To illustrate the historical slipperiness of the meaning of jazz, Blumenthal recalls what bassist Christian McBride said when asked whether Herbie Hancock’s “Chameleon,” from the 1973 Head Hunters album, was jazz: “It wasn’t then, but it is now.” “I thought that hit the nail on the head. At the time, it was a real controversy — had Herbie Hancock sold out? But now, no one would even question that ‘Chameleon’ is jazz.” Or he considers two recordings from 1964. “If you asked most jazz fans that year, ‘What is jazz?’, they would have said John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme. But if you asked a person on the street, they’d say Louis Armstrong’s ‘Hello Dolly.’ And they’d both be right!”