advocates like Handy are frustrated by the pace of change. |

Seth Handy does not have a long pony tail that snakes down the back of his rumpled hemp shirt, nor does he wear Birkenstocks to work. He does not drive a car covered with angry, peeling bumper stickers, and does not rail against the “establishment,” or “the man.”

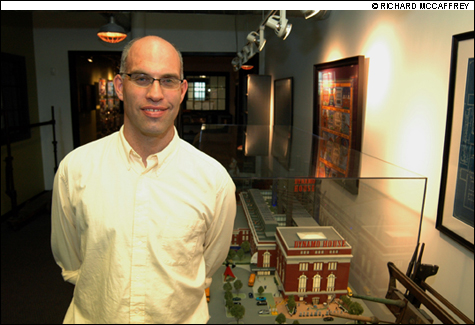

In fact, as a Harvard-educated project manager for Struever Brothers Eccles & Rouse, the Baltimore-based developer with billions of dollars in construction in an array of cities, Handy might be seen by some people as “the man.”

Yet Handy is a leading figure in the green design movement in Rhode Island. As the manager of Dynamo House, an ambitious new residential-retail project to be built near the former Narragansett Electric Plant in Providence, he is responsible for ensuring that the complicated project wins its green certification from the United States Green Building Council (USGBC), a nonprofit advocacy group in Washington, DC. If this happens following the project’s scheduled completion in 2009, Dynamo House will be among a handful of green buildings in Rhode Island recognized by the USGBC.

Why does this matter? It matters because standard buildings, according to the council, account for 65 percent of the electricity consumed by Americans and 36 percent of our total energy use — and they contribute significantly to greenhouse gas emissions. Not surprisingly, any comprehensive plan to curb global warming must take buildings into account.

In contrast, however, to the relatively fast-growing appreciation that many people have about the threat posed by climate change, Rhode Island continues to lag behind other states when it comes to making greater use of green design.

Proponents say that green design is not only an environmental issue, but also an economic necessity as energy prices continue to skyrocket. As Charles Lockwood, the author of Building the Green Way (Harvard Business Review, 2006), wrote last December in the financial magazine Barron’s, conventional buildings are poised to “become the real estate industry’s version of the buggy whip. Rapid and massive obsolescence has challenged the world’s commercial real estate markets before. When earlier innovations were introduced into commercial buildings — like central air-conditioning in the 1950s and 1960s — all properties lacking this innovation quickly became outmoded, and their value fell as top tenants headed for the nearest exits.”

The soul of a new building

Ten years ago, buildings like Dynamo House were not being constructed by real estate developers like Struever Brothers. Back then, green design remained the province of environmental advocates.

Green buildings were personal pet projects, back-to-the-land farm homes sagging under the weight of their solar panels, not massive for-profit urban developments.

All this has changed in the last few years. The concept of green design has become mainstreamed so quickly that a month rarely passes without some new article about the topic. A year ago, Vanity Fair, in its first “green issue,” devoted photo spreads to a group of leading green mayors and governors. Earlier this month, New York magazine spoofed the green mania with a series of imagined products, including a solar-powered bag, an oil-drum coffee table, and a carbon-neutral wedding.

Week by week, cities and states are enacting tougher laws and incentive packages to ensure that new construction is energy-efficient and less polluting. The Green Building Council, meanwhile, predicts that the percentage of green-certified buildings in the US will rise, from five to 10, by 2010.

Dynamo House epitomizes this kind of groundswell. The residential-retail complex is expected to use 15 percent-to-20 percent less energy than a comparable standard non-green building. This will be possible because of design features such as a green roof (think vegetation as insulation) and a projected installation of eight to 10 solar panels, as well as the more mundane use of energy-efficient lights and heating systems. The building won’t only use less energy — it will also be designed to encourage tenants to cut down on their greenhouse gas emissions by providing bike racks and public showers to encourage bicycle commuting.

Struever Brothers is not the only big developer in Rhode Island to believe that the additional construction costs of going green — usually less than three percent of the total project — will be more than paid for by the long-term maintenance savings.

Russell S. Preston, architectural designer at Providence-based Cornish Associates, says the company has halted design on some of its Rhode Island projects to learn what would be required to meet the criteria of the United States Green Building Council. This standard, known as the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program, is quickly becoming the international measuring stick for green design.

Completed projects, such as the Peerless Building in downtown Providence, may also be retrofitted with green design features in the future. “If it doesn’t increase value now, in 10 or 15 years, it’s going to be more valuable,” says Preston. “Our buildings are designed to be long-term investments.”